결명자 새싹의 재배 방법과 수확 시기에 따른 항산화 활성

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

To evaluate bioactivities of sicklepod sprout, total polyphenol and flavonoid contents, and antioxidative activity based on the amounts of aurantio-obtusin, and obtusifolin were measured during germination and growth.

Sicklepod sprouts were raised in grow boxes. Total polyphenol and flavonoid contents, and antioxidant activity were determined by established colorimetric methods. Aurantio-obtusin and obtusifolin were quantitatively analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography. As the harvest time increased, dry weight increased. The total polyphenol and flavonoid contents were the highest 9 days after sowing (DAS) with respectively valuse of 89.24 ± 3.41 ㎎·gallic acid equivalent/g and 57.31 ± 0.92 ㎎·catechin equivalent/g. At 9 DAS, antioxidant activity as measured using ABTS as the substrate was highest (IC50 164.93 ± 7.52 ㎍/㎖). Aurantio-obtusin and obtusifolin quantities were 1.029 ± 0.045 and 0.146 ± 0.005 ㎎/g, respectively, at 3 DAS. Among growth factors, irrigation interval and sowing density did not lead to significant variations. Considering sprout size and dry weight, a 6 h interval and 2.8 ea/㎠ were chosen.

Experimentally determined values were highest at 9 DAS. This finding should serve as a basis for the growth optimization of S. tora sprouts and their potential use as a health functional food.

Keywords:

Senna tora (L.), Antioxidant, Flavonoid, Irrigation Interval, Polyphenol, Sowing Density, Sprout서 언

결명자 [Senna tora (L.) Roxb, sicklepod]는 콩과 (Fabaceae) 의 북아메리카 원산지의 1년생 작물로 긴강남차, 결명차, 초결명, 마제결명 등으로 불린다 (Lee, 2006; Kim, 2008). 결명자는 고전 동양의학에서부터 사용되었는데, ‘종자는 가루내어 먹고 어린 가지와 잎은 나물로 먹으며 간병이 있는 사람의 열을 없애고 간기를 도와 간의 독열과 두풍을 치료하고 눈을 밝게한다’ 고 알려져 있으며 (Yoon and Kim, 2006), ‘맛은 쓰고 달며 성질은 서늘하다. 야맹증, 고혈압, 습관성 변비 등을 치료한다’ (Kim et al., 2004) 등의 기술이 있으며 주로 간, 변비 그리고 눈에 대한 치료에 주로 쓰였다.

현재 보고된 결명자의 성분으로는 aurantio-obtusin, cassiaside C, C2, B2, chryso obtusin, chryso obtusin-2-Oβ-D-glucoside, chrysophanol tetraglucoside, chrysophanol triglucoside, chrysophanol, emodin, glucoaurantio obtusin, gluco-obtusifolin, obtusifolin, obtusin, physcion, questin, rubrofusarin, torachryson, toralactone, toralactone gentiobioside 등이 있다 (NIFDSE, 2017).

이중 aurantio-obtusin은 결명자의 지표 성분 중 하나로, RAW264.7 cell에서 nitric oxide 및 prostaglandin E2의 생성을 감소시키고 cyclooxygenase-2, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin 6 등의 단백질을 억제하여 항염증 활성을 보였다 (Hou et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019b). 급성 폐 손상 마우스 모델에서 폐염증 반응을 약화시켜 폐염증질환 치료 가능성을 보였으며 (Kwon et al., 2018), 면역 글로불린 E 알레르기 매개 생쥐에서 비만세포 의존성 피부 아나필락시스를 차단하는 등의 효과를 보였다 (Kim et al., 2015).

결명자는 식품공전에 의거, 잎과 열매를 식용할 수 있는 작물임에도 주로 종자를 이용하고 이에 관련한 연구들이 주를 이루어 잎의 활용 사례를 찾아보기 어렵다 (Hwang, 2021; Tzeng et al., 2013; Hong et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2001). 일반적으로 작물의 순, 잎, 새싹 등은 플라보노이드, 폴리페놀, 항산화, 미백 등의 다양한 잠재적 효능을 가져 많은 연구들이 진행 중이다 (Kim et al., 2021; Lee and Kim, 2021; Jo et al., 2022; Kim, 2022).

특히 새싹은 종자에서 처음 터져 나오는 어린잎, 혹은 줄기를 말하는 것으로 발아하여 본 잎이 전개되지 않은 미숙한 상태의 어린 채소를 말한다 (Seo, 2017). 발아 시 종자는 곰팡이, 박테리아와 같은 외부 위험 요소 방어 기재로 비타민, 플라보노이드 등의 많은 합성물을 만들어 내는데 이로 인해 새싹이 종자보다 많은 영양학적 이점을 취할 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다 (Yiming et al., 2015).

앞서 언급한 바와 같이 결명자는 종자에 관한 연구가 주를 이루고 잎을 활용한 식품이나 관련 연구는 미비하다. 본 연구에서는 결명자 새싹의 활용 가능성을 알아보기 위해 폴리페놀 및 플라보노이드, 구성 성분 함량, 항산화 활성 등을 실험하였다. 이것을 바탕으로 최적 새싹 재배 방법을 구명하여 결명자 싹의 부가가치 증대와 기능성 식품으로써의 근거 자료를 마련하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 결명자 새싹 재배 조건 구명 및 특성조사

결명자 새싹의 재배는 아람종묘 (Seoul, Korea)에서 구매한 종자를 24 시간 침지한 후, 유공 트레이 (30 ㎝ × 35 ㎝)에 거즈면을 1 겹으로 깔고 컨테이너 내부에서 조명 및 환기가 되는 생육 상자에 파종하였다. 27 ± 2℃, 71.5 ± 4.2% 상대습도의 조건에서 Mist pump (EN6121S, Easy Garden Watering Co., Ltd, Ningbo, China)로 관수하여 9 일간 재배하였다.

관수 시간 구명은 간격을 달리하여 하루 3 회, 8 시간 간격, 4 회, 6 시간 간격, 6 회, 4 시간 간격으로 관수하였다. 관수량은 회당 2.7 ℓ로, 30 ㎝ × 35 ㎝의 면적이 충분히 젖고 먼지 및 포자 등의 오염원 세척을 위해 물이 트레이 아래로 흐르는 시간으로 하였다. 파종량 구명은 30 ㎝ × 35 ㎝의 면적 기준 각 100 g, 50 g, 25 g인 5873 립, 2908 립, 1440 립 3 반복 파종하였다.

일자별 새싹 재배 및 조건 구명에는 관수 6 시간 간격, 2908 립을 기준으로 재배하였다.

특성조사는 처리구당 20 주를 선발하여 총길이, 배축 두께, 자엽 길이, 자엽 너비를 디지매틱 켈리퍼스 (CD-15AX. Mitutoyo, Kanagawa, Japan)로 측정하였다. 총길이는 유근을 제외한 전체 길이, 배축두께는 유근 시작점에서 2 ㎜ 위, 자엽 길이 및 너비는 가장 긴 부분을 측정하였다.

2. 결명자 시료 추출물 제조

동결건조 후 분말화한 시료 5 g에 70% 에탄올 100 ㎖를 첨가하여 30 분 동안 초음파로 3 회 반복 추출한 후 여과 및 감압 농축 (N-1200A, Eyela, Tokyo, Japan)하였다. 추출물은 일자별 새싹, 대조군으로 종자 및 노지재배 순을 사용하였다.

대조군으로 사용된 종자는 새싹 재배와 같은 것을 분쇄하였고 노지 재배 순은 육묘이식하여 노지에서 45 일간 자란 어린잎을 사용하였다. 실험에 사용된 새싹은 자엽을, 순은 본엽 이후의 어린 잎을 칭하였다.

3. 총페놀 및 총플라보노이드 함량 측정

총페놀 함량은 Folin과 Denis (1912), Lee 등 (2019a)의 방법을 변형시켜 사용하였다. 각각 제조된 추출물을 1,000 ppm의 농도로 희석한 희석액 50 ㎕와 1 N의 folin-ciocalteu 시약 25 ㎕를 혼합하여 3 분간 반응시킨 후 20%의 Na2CO를 50 ㎕ 수준으로 첨가하여 반응을 종결한 후 10 분 뒤에 microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)를 이용하여 725 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. Gallic acid를 이용하여 표준 곡선을 작성한 뒤 3 반복으로 측정된 결과값의 평균으로 함량을 산출하였다.

총플라보노이드 함량은 Moreno 등 (2000)의 방법을 변형하여 사용하였다. 각각 제조된 추출물을 2,500 ppm의 농도로 희석한 희석액 125 ㎕와 5%의 NaNO2 용액을 37.5 ㎕ 혼합하여 5 분 동안 반응시킨 후, 다시 10%의 AlCl3·6H2O를 첨가하여 6 분 동안 반응시키고, 1 M의 NaOH를 250 ㎕ 수준으로 첨가하여 11 분 동안 반응시킨 후 microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)를 이용하여 510 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. Catechin을 이용하여 표준곡선을 작성한 뒤 3 반복으로 측정된 각 시료의 결과값을 평균으로 정량하였다.

4. 항산화 활성 측정

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) 라디칼 소거 활성은 Lee와 Lee (2004)의 방법을 변형하여 사용하였다. 각 결명자 추출물의 농도별 시료 40 ㎕와 0.2 mM DPPH solution 160 ㎕를 암조건에서 30 분 동안 반응시킨 후 microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)를 이용하여 517 ㎚의 파장으로 측정하였다. 결과값은 흡광도를 50% 감소시킬 수 있는 시료 소요량 (IC50)을 측정하였고 3 회 반복 측정한 결과값의 평균으로 나타내었으며 대조군으로 ascorbic acid를 사용하였다.

[2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] (ABTS)는 Re 등 (1999) 및 Lee 등 (2019a)의 방법을 참고하여 측정하였다. 7 mM ABTS와 2.45 mM potassum peroxo-disulfate를 혼합한 뒤 12 시간 동안 차광하여 라디칼 생성을 유도하였다. ABTS 혼합액을 734 ㎚의 파장에서 흡광도를 측정하여 optical density (OD734) 값이 0.7 ± 0.02가 되도록 에탄올로 희석하여 제조한 ABTS solution 180 ㎕에 각 결명자 추출물 농도별 시료 20 ㎕를 첨가하여 5 분 간 반응시킨 뒤 microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)로 734 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 결과값은 흡광도를 50% 감소시킬 수 있는 시료 소요량 (IC50)을 측정하였고 3 회 반복 측정한 결과값의 평균으로 나타내었으며 대조군으로 Trolox를 사용하였다.

5. Aurantio-obtusin 및 obtusifolin의 분석

Aurantio-obtusin과 obtusifolin의 측정은 Agilent Technologies 1290 series (Aglient Technology Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) 기기를 사용하였고 컬럼은 YMC Pack Pro C18 (4.6 ㎜ × 250 ㎜, 5 ㎛,. YMC Inc., Wilmington, NC, USA)를 이용하였다.

이동상은 0.1% phosphoric acid을 포함한 water (mobile phase A, JT Baker, Deventer, Netherlands)와 acetonitrile (mobile phase B, JT Baker, Deventer, Netherlands)를 사용하였고 gradient system을 적용하여 0 분에서 25 분까지 mobile phase A를 60%, 20 분에서 25 분까지 mobile phase A를 0%로 조정하여 분석을 실시하였다. Flow rate은 1 ㎖/min으로 고정하였고 injection volume은 10 ㎕로 하였으며 column oven의 온도는 35℃로 고정하였고, 278 ㎚에서 측정하였다.

Aurantio-obtusin과 obtusifolin (ChemFaces, Hubei, China) 을 0.195 – 100 ppm의 농도로 10 point 분석하여 각 y = 56.897 x - 3.899 (R2 = 0.9999), y = 69.086 x + 20.291 (R2 = 0.9999) 검량선을 작성하였다. 분석 시료는 10 ㎎/㎖로 MeOH에 용해 후 0.45 ㎛ 실린지 필터 (Pall, Port Washington, NY, USA)에 여과하여 사용하였다.

6. 통계처리

실험의 결과는 평균과 표준편차 (means ± SD)로 나타내었고, 통계처리는 SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (Statistical analysis system, 2009, SAS Institute Inc., Cray, NC, USA)를 사용하여 ANOVA 분석을 수행하였고, 처리구 간 유의성 검정은 Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT)로 5% 수준에서 실시하였다 (p < 0.05).

결과 및 고찰

1. 발아 일수별 새싹의 생육

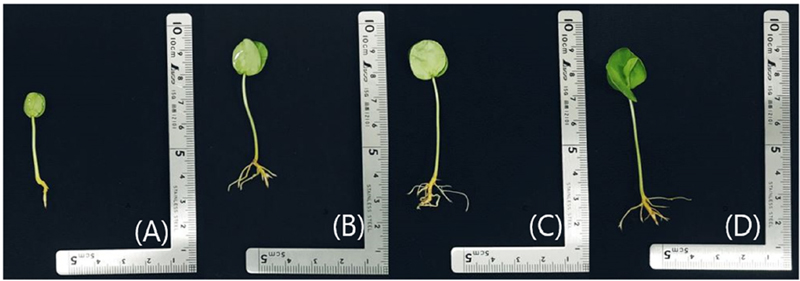

발아 일수별 생육을 본엽이 처음으로 발현된 9 일차까지 2 일 간격으로 조사해 본 결과, 배축의 길이는 일자가 증가할수 록 길어지고 배축의 두께는 반대로 감소하였다. 자엽의 길이 및 너비는 파종 후 경과일수 (days after sowing; DAS) 7 일에서 가장 컸으나 9 DAS와 유의적인 차이는 없었다. 건물 중은 일자가 증가할수록 커졌으며 건물율은 5 DAS를 기점으로 7 DAS에서 약 0.62 배 감소하였고 9 DAS에 다시 증가하였다 (Table 1).

3 DAS 이후로 잎의 비대 생장 및 뿌리의 분화가 관찰되고 9 DAS부터 본엽이 전개되는 것을 관찰할 수 있었다 (Fig. 1). 콩과작물은 발아 중 호흡을 통한 탄수화물 감소로 인해 건조중량이 감소하고 단백질 함량이 증가되어진다고 보고된 바 (Uppal and Bains, 2012), 결명자 새싹 또한 5 DAS와 7 DAS 사이 건물률이 급격히 줄어들어 같은 양상으로 나타낸다고 판단된다.

2. 발아 일수별 항산화

총페놀 및 총플라보노이드 함량 (total polyphenol and total flavonoid contents, TPFC)은 발아 직후 3 DAS에서 증가하였다가 감소 후 9 DAS까지 증가하는 경향을 보였다. 9 DAS의 TPFC은 종자에 비해 각 1.37, 1.1 배 증가하였다 (Table 2). DPPH 및 ABTS의 IC50 값 또한 발아 직후에 항산화 활성이 낮아지고 일수가 경과할수록 활성이 높아지는 경향을 보였다 (Table 3).

Total polyphenol and total flavonoid contents of sicklepod sprout extracts by different harvest dates.

폴리페놀과 플라보노이드는 전자공여를 통해 자유 라디칼을 소거하여 항산화 활성을 나타내는 물질로 (Tsao, 2010; Horozic, 2023) 결명자 싹 추출물의 TPFC는 항산화 결과에 영향을 나타낸 것으로 해석된다. 일반적으로 종자는 발아 시에 외부 위험 요인에 대한 보호작용으로 여러 가지 생리활성 물질을 합성하며 페놀과 플라보노이드의 함량은 시기에 따라 효소 활성 및 대사산물 합성에 따라 함량에 차이가 생긴다 (Cheng et al. 2012; Kobayashi et al.. 2019).

율무, 병아리콩, 완두콩, Lupin 등이 발아 이후 TPFC가 증가하였고 (Duenas, 2009; Lee et al., 2019a; Wang et al., 2023; Sofi et al., 2023), Balbaa 등 (1974)과 Di Bella 등 (2020) 은 새싹에서 순으로 갈수록 TPFC가 감소한다 보고하였다.

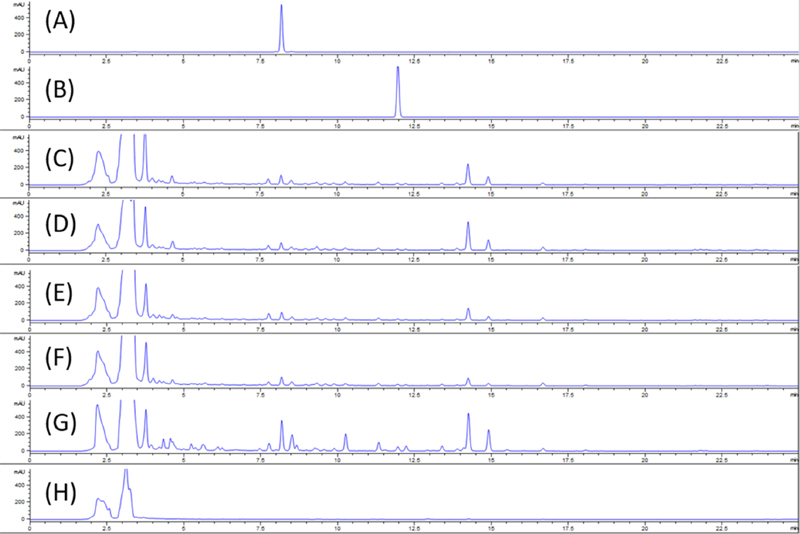

결명자 종자 주요 성분인 aurantio-obtusin 및 obtusifolin은 anthraquinone 계열의 물질로 구조 및 특성상 항산화 활성을 나타내는 물질이다 (Xu et al., 2013; Zhuang et al., 2016). Aurantio-obtusin과 Obtusifolin은 종자에서 함량이 가장 높으며 발아와 함께 그 함량이 1/3로 줄어드는 것을 확인할 수 있는데 (Table 4), 종자 추출물의 높은 항산화 활성은 이에 기인한 것으로 판단된다.

Abundance of aurantio-obtusin and obtusifolin in sicklepod sprout extracts by different harvest dates.

노지재배 순의 경우, TPFC 값이 새싹의 1.16 배 – 1.47 배로 함량이 증가하여 노지재배 순 또한 항산화 기능성 식품으로서의 활용 가능성을 시사한다고 하겠다.

3. 최적 새싹 재배 조건 구명

수확량, 폴리페놀, 플라보노이드 함량 및 항산화 결과를 고려하였을 때 결명자 새싹의 최적 재배 일수는 9 일이 적합하다고 판단하여 9 일간 최적 새싹 재배 조건을 살펴보았다.

적정한 관수 간격을 알아보기 위해 회당 2.7 ℓ씩 하루 4 시간, 6 시간, 8 시간 간격으로 관수한 결과, 하루 물의 총량은 각 16.2 ℓ, 10.8 ℓ, 8.1 ℓ로 배축의 길이와 두께, 자엽의 길이와 너비는 모두 4 시간 간격 처리구에서 가장 높은 값을 보였다. 건물중의 경우 8 시간 간격의 관수에서 가장 높은 값을 보였으나 통계적 유의차를 보이지 않았다 (Table 5).

HPLC chromatogram of aurantio-obtusin and obtusifolin from sicklepod extract.(A); aurantio-obtusin, (B); obtusifolin, (C); 3 DAS-E, (D); 5 DAS-E, (E); 7 DAS-E, (F); 9 DAS-E, (G); SE, (H); ESCF, DAS-E; extract of sicklepod sprout by different days after sowing, SE; seed extract of sicklepod, ESCF; extract of sicklepod shoot grown in field (harvested in June).

환기팬이 있는 조건에서 처리구별 공중 상대습도가 큰 차이를 보이지 않았는데 이것은 발아 트레이의 수분이 공중 습도를 유지한 것으로 판단되며 이로 인해 관수 간격이 길어질수록 트레이에 충분한 습윤 환경이 조성되지 못해 건조 스트레스가 식물체 내 수분 포텐셜을 감소시켜 세포분열 및 비대 등 조직 발달이 억제된 것으로 보인다 (Lee et al, 2020).

수분 스트레스로 인해 항산화 활성 물질이 증가된다는 보고가 있으나 (Chiara et al, 2020), 이번 연구에서는 일자별 항산화 실험 후 새싹 재배 요건에 대한 실험이 이루어져 재배조건 별 항산화 물질 차이에 대해서는 고려하지 않았다. 이에 관해서는 추가 실험이 필요할 것으로 보이며, 이번 결과에서는 충분한 잎 성장과 수확량, 물 소요량 등을 고려하였을 때 6시간 간격의 관수 처리가 가장 적합한 것으로 판단하였다.

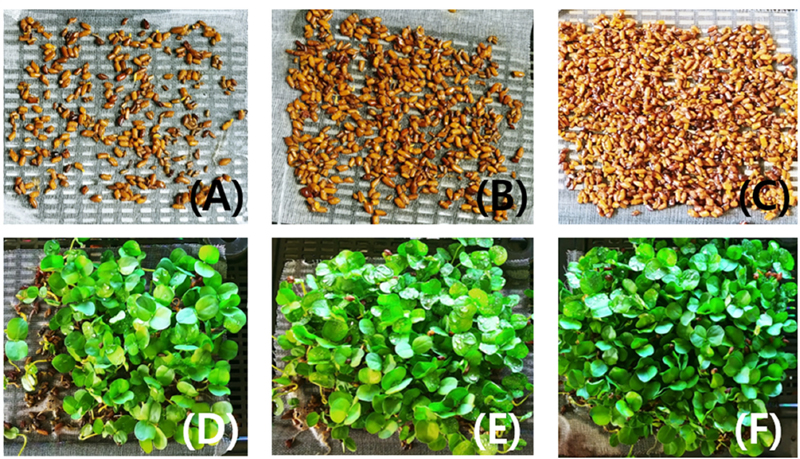

적정 재식밀도를 알아보기 위해 30 ㎝ × 35 ㎝ 면적 기준 각 100 g, 50 g, 25 g인 5873 립, 2908 립, 1440 립을 파종 하였고 단위면적 당 립수로 환산한 결과 각 면적당 파종 립수는 5.6 ea/㎠, 2.8 ea/㎠, 1.4 ea/㎠로 확인되었다.

배축의 길이는 2.8 ea/㎠, 5.6 ea/㎠에서, 나머지 측정 항목에서는 1.4 ea/㎠에서 가장 큰 측정 결과값을 보였으나 통계적 유의차는 없었다 (Table 6). 면적 당 파종량에 따라 5.6 ea/㎠로 갈수록 종자의 겹침 정도가 심해지고, 생육 시 종피 탈락이 되지 않은 자엽을 관찰할 수 있었다 (Fig. 3).

The appearance of sicklepod sprout based on seeding density immediately and 9 days after sowing(A); Seed 1.4 ea/c㎠, (B); Seed 2.8 ea/㎠, (C); Seed 5.6 ea/㎠, (D); 9 DAS 1.4 ea/㎠, (E); 9 DAS 2.8 ea/㎠, (F); 9 DAS 5.6 ea/c㎠, DAS; days after sowing.

밀식은 수확량 증대로 이어져 단기간 다수확에 도움이 될 수 있으나, 파종 밀도에 따라 식물의 생육에는 차이가 생긴다. 숙주는 밀식 재배 시 수확량이 증대했고, 들깨 싹은 재식밀도에 따라 수확량과 싹의 길이 등의 차이를 보였다. 또한 쌀의 경우는 적정 파종밀도에 비해 밀식으로 재배한 경우 잎의 건중이 줄어드는 것을 확인하였다. (Turbin et al, 2014; Liu et al, 2017; Wu et al, 2020).

단위면적당 생산량 및 수확에 용이한 배축 길이를 고려한 경우 2.8 ea/㎠가 가장 적합한 파종밀도라 판단되었다.

현재 작물의 비 식용부위, 새싹, 기타 부산물 등 사용하지 않는 부위 및 형태에 대한 활용 연구들이 진행 중이나 결명자의 쓰임과 잎에 관한 연구는 미비하였다. 본 연구는 결명자 수확 일자별 새싹의 항산화 활성, 플라보노이드 및 폴리페놀 총량, 함유 성분량을 알아보았고 그 결과 9 DAS가 가장 적합하다 판단하였다. 9 DAS 새싹의 재배 조건으로 적정 관수 간격 및 파종 밀도를 알아본 결과 6 시간 간격 관수, 2.8 ea/㎠를 적정 밀도로 설정하였다. 이번 결과를 통하여 주목받지 않던 결명자 싹에 대한 활용이 새로이 주목받을 것으로 기대한다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 농촌진흥청 연구사업(과제번호: PJ01512201)의 지원에 의해 이루어진 결과로 이에 감사드립니다.

References

-

Balbaa SI, Zaki AY and El Shamy AM. (1974). Qualitative and quantitative study of the flavonoid content of the different organs of Sophora Japonica at different stages of development. Planta Medica. 25:325-330.

[https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1097951]

-

Cheng S, Feng XU, Linling LI, Cheng H and Zhang W. (2012). Seasonal pattern of flavonoid content and related enzyme activities in leaves of Ginkgo biloba L. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 40:98-106.

[https://doi.org/10.15835/nbha4017262]

-

Chiara A, Carmen A, Stefania DP and Veronica DM. (2020) Light and low relative humidity increase antioxidants content in mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) sprouts. Plants. 9:1093. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7570258/, (cited by 2023 Nov 14).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9091093]

-

Di Bella MC, Niklas A, Toscano S, Picchi V, Romano D, Lo Scalzo R and Branca F. (2020). Morphometric characteristics, polyphenols and ascorbic acid variation in Brassica oleracea L. novel foods: Sprouts, microgreens and baby leaves. Agronomy, 10:782. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/10/6/782, (cited by 2023 Sep. 17).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10060782]

-

Duenas M, Hernandez T, Estrella I and Fernandez D. (2009). Germination as a process to increase the polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of lupin seeds(Lupinus angustifolius L.). Food Chemistry. 117:599-607.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.051]

-

Folin O and Denis W. (1912). On phosphotungstic-phosphomolybdic compounds as color reagents. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 12:239-243.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)88697-5]

-

Hong KH, Um MY, Ahn J and Ha TY. (2012). Effect of Cassia tora extracts on D-galactosamine-induced liver injury in rats. Korean Journal of Food and Nutrition. 25:546-553.

[https://doi.org/10.9799/ksfan.2012.25.3.546]

-

Horozic E, Kolarevic L, Bajic M, Alic L, Babic S and Ahmetasevic E. (2023). Comparative study of antioxidant capacity, polyphenol and flavonoid content of water, ethanol and water-ethanol Hibiscus extracts. European Journal of Advanced Chemistry Research. 4:13-16.

[https://doi.org/10.24018/ejchem.2023.4.2.130]

-

Hou J, Gu Y, Zhao S, Huo M, Wang S, Zhang Y, Qiao Y, and Li X. (2018). Anti-inflammatory effects of aurantio-obtusin from seed of Cassia obtusifolia L. through modulation of the NF-κB pathway. Molecules. 23:3093. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/23/12/3093, (cited by 2023 Aug. 24).

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123093]

- Hwang JK. (2021). Cassia tora seed extract alleviates hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury. Ph. D. Thesis. Kyung Hee University. p.1-29.

- Jo S, Kim JE and Lee NH. (2022). Whitening and anti-oxidative constituents from the extracts of Hydrangea petiolaris leaves. Journal of Society of Cosmetic Scientists of Korea. 48:123-134.

- Kim CM, Shin MG, Ahn DK and Lee KS. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Oriental Herbal Medicine. Jeongdam, Seoul, Korea. p.153.

- Kim IC. (2022). Evaluation on the whitening effect of Nypa fruticans wurmb extracts. Journal of the Korean Applied Science and Technology. 39:462-470.

-

Kim JY, Hwang BS, Kwon SH, Jang M, Kim GC, Kang J and Hwang IG. (2021). Various biological activities of extracts from Deodeok(Codonopsis lanceolata Trautv.) buds. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition. 50:10-15.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2021.50.1.10]

-

Kim MS, Lim SJ, Lee HJ and Nho CW. (2015). Cassia tora seed extract and its active compound aurantio-obtusin inhibit allergic responses in IgE-mediated mast cells and anaphylactic models. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 63:9037-9046.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03836]

- Kim TJ. (2008). Wild flowers and resources plants in Korea. Seoul National University Press, Seoul, Korea. p.438.

-

Kobayashi T, Kurata R and Kai Y. (2019). Seasonal variation in the yield and polyphenol content of sweet potato(Ipomoea batatas L.) foliage. The Horticulture Journal. 88:270-275.

[https://doi.org/10.2503/hortj.UTD-025]

-

Kwon KS, Lee JH, So KS, Park BK, Lim H, Choi JS and Kim HP. (2018). Aurantio-obtusin, an anthraquinone from cassiae semen, ameliorates lung inflammatory responses. Phytotherapy Research. 32:1537-1545.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6082]

- Lee DJ and Lee JY. (2004). Antioxidant activity by DPPH assay. Korean Journal of Crop Science. 49:187-194.

-

Lee HJ, Lee JH, Jung JT, Lee YJ, Oh MY, Chang JK, Jeong HS and Park CG. (2019a). Changes in free sugar, coixol contents and antioxidant activities of adlay sprout(Coix lacryma-jobi L. var. ma-yuen Stapf.) according to different growth stage. Korean Journal of Medicinal Crop Science. 27:339-347.

[https://doi.org/10.7783/KJMCS.2019.27.5.339]

- Lee KH, Jang JH, Woo KW, Nho JH, Jung HK, Cho HW, Yong JH, and An BK. (2019b). Anti-inflammatory effects of aurantio-obtusin isolated from Cassia tora L. in RAW264.7 cells. Korean Journal of Pharmacognosy. 50:11-17.

-

Lee KH, Lee SH, Yeon ES, Chang WB, Kim JH, Park JH, Han GH, Park JH, Kim SJ and Sa TM. (2020). Effect of irrigation frequency on growth and functional ingredient contents of Gynura procumbens cultivated in hydroponics system. Korean Journal of Soil Science and Fertilizer. 53:175-185.

[https://doi.org/10.7745/KJSSF.2020.53.2.175]

-

Lee SM and Kim CD. (2021). Antioxidant effect of leaf, stem, and root extracts of Zingiber officinale as cosmetic materials. Asian Journal of Beauty and Cosmetology. 19:23-33.

[https://doi.org/10.20402/ajbc.2020.0106]

- Lee YN. (2006). New flora of Korea. Kyohaksa, Seoul, Korea. p.598.

-

Liu Q, Zhou X, Li J and Xin C. (2017). Effects of seedling age and cultivation density on agronomic characteristics and grain yield of mechanically transplanted rice. Scientific Reports. 7:14072. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-14672-7, (cited by 2023 Aug. 22).

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14672-7]

-

Moreno MIN, Isla MI, Sampietro AR and Vattuone MA. (2000). Comparison of the free radical-scavenging activity of propolis from several regions of Argentina. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 71:109-114.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00189-0]

- National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation(NIFDSE). (2017). Cassiae Semen. National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation, Ministry of Food and Drug Dafety, Cheongju, Korea. https://nifds.go.kr/nhmi/main.do, (cited by 2020 Oct. 13).

-

Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M and Rice-Evans C. (1999). Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 26:1231-1237.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3]

- Seo WD. (2017). RDA interrobang; Comprehensive information on seedlings. Rural Development Administration. Wanju, Korea. https://nongsaro.go.kr/portal/ps/psv/psvr/psvrc%20/rdaInterDtl.ps?&menuId=PS00063&cntntsNo=207811, (cited by 2023 Aug. 29).

-

Sofi SA, Rafiq S, Singh J, Mir SA, Sharma S, Bakshi P, McClements D J, Khaneghah AM and Dar BN. (2023). Impact of germination on structural, physicochemical, techno-functional, and digestion properties of desi chickpea(Cicer arietinum L.) flour. Food Chemistry. 405:135011. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308814622029739, (cited by 2023 Sep. 6).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.135011]

-

Tsao R. (2010). Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary polyphenols. Nutrients. 2:1231-1246.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2121231]

-

Turbin VA, Sokolov AS, Kosterna-Kelle EA and Rosa RS. (2014). Effect of plant density on the growth, development and yield of brussels sprouts(Brassica oleracea L. var. gemmifera L.). Acta Agrobotanica. 64:51-58.

[https://doi.org/10.5586/aa.2014.049]

-

Tzeng TF, Lu HJ, Liou SS, Chang CJ and Liu IM. (2013). Cassia tora(Leguminosae) seed extract alleviates high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 51:194-201.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2012.09.024]

-

Uppal V and Bains K. (2012). Effect of germination periods and hydrothermal treatments on in vitro protein and starch digestibility of germinated legumes. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 49:184-191.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-011-0273-8]

-

Wang L, Li X, Gao F, Liu Y, Lang S, Wang C and Zhang D. (2023). Effect of ultrasound combined with exogenous GABA treatment on polyphenolic metabolites and antioxidant activity of mung bean during germination. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 94:106311. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1350417723000238, (cited by 2023 Aug. 27).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106311]

-

Wu CH, Hsieh CL, Song TY and Yen GC. (2001). Inhibitory effects of Cassia tora L. on benzo[a]pyrene-mediated DNA damage toward HepG2 cells. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49:2579-2586.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf001341z]

- Wu L, Deng Z, Cao L and Meng L. (2020). Effect of plant density on yield and quality of Perilla sprouts. Scientific Reports. 10:9937. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-67106-2, (cited by 2023 Sep. 4).

-

Xu SC, Ren Y, Wan L, Li WK, Wong NB, Zhang JX, Liao Q and Ji L. (2013). DFT Insight into the UV-Vis spectra and radical scavenging activity of aurantio-obtusin. Journal of Theoretical and Computational Chemistry. 12:1350024. https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/abs/10.1142/S0219633613500247, (cited by 2023 Sep. 16).

[https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219633613500247]

-

Yiming Z, Hong W, Linlin C, Xiaoli Z, Wen T and Xinli S. (2015). Evolution of nutrient ingredients in tartary buckwheat seeds during germination. Food Chemistry. 86:244-248.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.115]

- Yoon SH and Kim HJ. (2006). Donguibogam. Donguibogam Publishing Company, Seoul, Korea. p.297-2189.

- Zhuang SY, Wu ML, Wei PJ, Cao ZP, Xiao P and Li CH. (2016). Changes in plasma lipid levels and antioxidant activities in rats after supplementation of obtusifolin. Planta Medica. 82:539-543.