아프리칸 메리골드 추출물의 신경염증 억제 효과

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

To discover novel natural compounds for controlling neuroinflammatory responses, we screened a plant library from Southeast Asia and found African marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) as a candidate. Although the flowers and leaves of T. erecta have been used in traditional medicine for fever reduction, hemostasis, and antiseptic effects, their potential for alleviating neuroinflammation has not been examined scientifically.

T. erecta extract inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced interleukin (IL)-1β protein expression in murine BV2 microglial cells and in primary microglia. The mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were dose-dependently reduced by T. erecta extract. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) was suppressed by T. erecta extract, indicating that T. erecta inhibited the expression of inflammatory mediators by inhibiting the transcriptional activation of STAT3 and NF-κB.

Overall, our results demonstrate the potential of T. erecta to be developed as a therapeutic agent for treating neurodegenerative diseases by controlling excessive neuroinflammatory responses

Keywords:

Tagetes erecta L., Lipopolysaccharide, Microglia, Neuroinflammation서 언

중추신경계의 면역은 중추신경계에만 존재하는 것으로 알려진 미세아교세포 (microglia)와 별아교세포 (astrocyte)에 의해 조절되는 것으로 알려져 있다 (Gehrmann et al., 1995). 뇌를 비롯한 중추신경계의 급성 염증반응은 감염과 독성 물질, 비정상적인 단백질의 축적 등에 의한 손상으로부터 신경세포를 보호하는 역할을 하지만, 제대로 조절되지 않게 되면 만성적인 염증반응으로 발전할 수 있다 (Gehrmann et al., 1995; Venneti et al., 2009).

만성적인 염증반응은 미세아교세포와 별아교세포를 활성화하여 interleukine (IL)-1β와 IL-6 같은 염증성 사이토카인(pro-inflammatory cytokine)과 tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)와 같은 염증 매개 인자의 분비를 촉진한다 (Gehrmann et al., 1995). 알츠하이머병(Alzheimer’s disease)을 비롯한 파킨슨병 (Parkinson’s disease), 다발성 경화증 (multiple sclerosis)과 같은 퇴행성 뇌신경 질환에서는 만성 신경염증 반응으로 인한 신경세포의 손상과 사멸이 관찰된다 (Jacobs et al., 2012). 따라서 만성 신경염증 반응이 퇴행성 뇌신경 질환의 병인 혹은 병리에 중요할 것이라고 여겨지게 되면서 미세아교세포의 과도한 활성화를 조절하기 위한 방법에 대한 연구가 다양하게 이루어지고 있다.

미세아교세포는 뇌의 항상성과 가소성 (plasticity)를 조절함과 동시에 세포 손상과 감염 등의 이상을 감지하는 역할을 한다 (Gehrmann et al., 1995). 미세아교세포는 손상된 신경세포가 분비하는 손상 연관 분자유형 (damage-associated molecular pattern, DAMP)이나 별아교세포에서 분비하는 염증성 사이토카인, misfolding된 단백질, 감염에 의한 병원체 연관 분자유형 (pathogen-associated molecular pattern, PAMP) 등의 신호를 인지하여 활성화된다 (Kumar, 2019). 활성화된 미세아교세포는 혈액-뇌 장벽 (blood-brain barrier)의 투과성을 변화시켜 백혈구 (leukocyte)가 중추신경계로 들어오도록 하여 국소 염증반응을 촉발한다 (Kumar, 2019).

알츠하이머병과 파킨슨병 동물 모델을 이용한 연구에서 미세아교세포가 과도하게 활성화된다는 것이 확인되었으며, 이러한 결과들은 미세아교세포가 이들 병과 밀접한 관련이 있을 것이라는 주장을 뒷받침해 준다 (Dickson et al., 1993; McGeer et al., 1988). 따라서 미세아교세포의 과도한 활성화와 신경염증 반응을 억제하는 것이 퇴행성 뇌신경 질환의 완화 혹은 치료 방법이 될 수 있을 것으로 예상된다. 이를 위해 본 연구에서는 천연물 라이브러리를 활용하여 신경염증 반응을 억제할 수 있는 소재를 발굴하고자 하였다.

동북아시아 지역 자생식물의 항염 효능에 대한 연구는 기존에 많은 연구가 이루어지고 있어, 그 외 지역의 해외생물소재를 중심으로 스크리닝을 진행하였다. 그 결과 아프리칸 메리 골드 (Tagetes erecta L.)에서 우수한 항염 효능이 있는 것을 확인하였는데, 이는 초롱꽃목 국화과 천수국속 식물로 멕시코가 원산지이며 황색, 담황색 등의 꽃을 피우는 식물이다 (Sing et al., 2020).

아프리칸 메리골드의 꽃은 루테인 (lutein)을 다량으로 함유하고 있어 식품용 색소와 눈 건강을 위한 건강기능성 식품의 원료로 널리 사용되고 있다 (Pratheesh et al., 2009). 또한 꽃이나 잎에서 추출된 에센셜 오일은 플라보노이드 (flavonoid), 알칼로이드 (alkaloid), 지방산 (fatty acid), 폴리아세틸렌 (polyacetylene), α-terthienyl, thiophene 등의 다양한 활성 성분이 포함되어 있는 것이 여러 논문에서 보고된 바 있다 (Li-Wei et al., 2011; Dasgupta et al., 2012).

아프리칸 메리골드의 꽃은 원산지인 남미에서 오래전부터 해열, 간질 발작, 지혈제, 위장질환, 간질환 등에 민간요법으로 활용되었으며, 잎은 살균제와 근육통, 신장질환, 치핵과 종기 치료 등에 활용되었다 (Sing et al., 2020). 하지만, 아프리칸 메리골드의 신경염증 억제 효과에 관한 연구는 보고된 바 없다.

본 연구는 미세아교세포주인 BV2 세포주와 primary microglia에 lipopolysaccharide (LPS)를 처리하여 염증반응을 유도하고, 아프리칸 메리골드 (T. erecta) 추출물이 이를 억제할 수 있는지 확인하기 위하여 실시되었다.

재료 및 방법

1. 실험재료

아프리칸 메리골드 (Tagetes erecta L.)의 잎 메탄올 추출물은 한국생명공학연구원 해외생물소재센터에서 분양받아 사용하였다 (분양번호; FBM225-019).

아프리칸 메리골드의 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)은 방글라데시에서 수확한 아프리칸 메리골드의 잎을 99.9% 메탄올로 3 일 간, 2 시간 간격으로 15 분 동안 초음파 처리하였다. 추출물은 여과 후 회전증발기 (N-1000SWD, EYELA, Tokyo, Japan)를 사용하여 농축하고, 건조기 (Modulspin 40, Biotron Co., Bucheon, Korea)로 건조된 상태로 분양받았다. TE는 dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA)로 20 - 100 ㎎/㎖ 농도가 되도록 희석하여 실험에 사용하였다.

2. 세포배양

마우스 미세아교 세포주인 BV2 세포주는 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlas Biologicals, Fort Collins, CO, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA)이 첨가된 DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) 배지를 사용하여 37℃, 5% CO2 incubator (MCO-18AIC, Sanyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan)에서 배양하였다.

Primary microglia는 C57BL/6 마우스 (P0-P1)로부터 분리·배양하였고, 참고논문의 방법을 참고하였다 (Yamanaka et al., 2012). 임신한 C57BL/6 마우스는 오리엔트바이오 (Seongnam, Korea)에서 구입하였다. 갓 태어난 마우스로부터 분리된 신경교세포는 10% bovine calf serum (BCS) (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA)이 첨가된 DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) 배지를 사용하여 37℃, 5% CO2 incubator (MCO-18AIC, Sanyo, Tokyo, Japan)에서 배양하였다. 14 일 후 shaker (2D-400, FINEPCR, Gunpo, Korea)를 이용하여 180 rpm에서 1 시간 동안 쉐이킹하여 떨어진 세포들을 모아 사용하였다.

동물실험에 관한 내용은 강원대학교 동물실험윤리위원회 (Institutional Animal Care and Use Commitee, IACUC 승인번호: 191107-2)에서 승인을 받아 진행하였다.

3. Cell viability assay

BV2 세포주를 12 well plate에 24 시간 배양 후, TE를 농도, 시간별로 처리하였다. Pipette을 이용하여 세포를 떨어뜨리고 동량의 trypan blue와 섞어준 후 hemocytometer (Neubauer Improved, Paul Marienfeld GmbH & Co. KG, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany)를 이용하여 살아있는 세포수를 측정하였다. 세포생존율은 다음과 같은 식으로 환산하여 계산하였다.

4. Western blot

BV2 세포주와 primary microglia를 배양한 6 well plate의 배지를 제거하고, lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, protease inhibitor cocktail]를 이용하여 세포를 lysis하고 정량하였다. SDS-PAGE 후 단백질은 nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Inc., Hercules, CA, USA)으로 transfer하였다. 멤브레인은 5% 탈지분유 (non-fat dried milk)로 30분 blocking 하였다.

Anti-mouse IL-1β (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), anti-phospho-STAT3, anti-STAT3, anti-phospho-ERK, anti-ERK, anti-phospho-SAPK/JNK, anti-SAPK/JNK, anti-phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA, USA), anti-NF-κB p65, anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA)의 1차 항체는 4℃에서 16시간 이상 incubation 하였다. 이후 anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked, anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA, USA) 또는 anti-goat IgG, HRP-linked 2차 항체 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA)를 이용하여 단백질 발현 여부를 확인하였다.

5. RNA 분리 및 qRT-PCR

BV2 세포주와 primary microglia를 배양한 6 well plate의 배지를 제거하고, RiboEx (GeneAll Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea)를 500 ㎕ 처리하고 상온에서 5 분 반응시키고 1.5 ㎖ tube로 옮겼다. Chloroform을 100 ㎕ 첨가하고 상온에서 2 분 반응시켰다. 원심분리기 (5415 R, Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY, USA)로 15 분 동안 원심분리 (12,000 × g, 4℃)를 진행하고, 상등액을 새로운 1.5 ㎖ tube로 옮겼다. 동량의 isopropyl alcohol을 넣어 섞어주고 상온에서 10 분 방치 후 다시 10 분간 원심분리한 뒤 상등액을 제거하였다. Pellet은 75% ethanol 1 ㎖로 파이펫팅하여 세척하고 5 분간 원심 분리 (7,500 × g, 4℃) 하였다.

RNA pellet을 diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)를 처리한 dH2O (RNase-free water)에 녹이고 nanodrop 2000 (ND-2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)으로 RNA 농도를 확인한 뒤 −80℃에 보관하였다. 18s와 28s ribosomal RNA를 전기영동으로 확인하고 이후 실험을 진행하였다. ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan)을 이용하여 0.5 ㎍의 RNA를 cDNA로 역전사하였다. 이후 qPCR은 SYBR Green real-time PCR Master Mix (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan)을 이용하여 수행하였다.

PCR 조건은 95℃에서 5 분간 pre-denaturation, 95℃에서 30 초 denaturation, 58℃에서 30 초 annealing, 72℃에서 30초 extension의 조건으로 40 cycles 수행하였다. qPCR 과정은 Table 1의 primer를 사용하여 AriaMX (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA)에서 수행되었다. 결과는 상대정량 분석을 위해 β-actin으로 정규화하였다.

6. Reporter gene assay

BV2 세포주를 6 well plate에서 하루 동안 배양하고, 다음날 NF-κB-luciferase vector (firefly reporter)과 pTK-luciferase vector (renilla reporter)를 Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)으로 transfection하였다. 24 시간 후 TE 100 ㎍/㎖과 300 ㎍/㎖을 30 분간 전처리하고, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA)를 50 ng/㎖의 농도로 6 시간 처리하였다.

Dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA)를 이용하여 세포를 lysis하고 SpectraMax L microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)로 발광도를 측정하였다. firefly activity는 renilla activity로 정규화하였다.

7. 통계처리

Western blot의 densitometric scan은 ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA)로 정량화되었다. 모든 통계 분석은 SPSS (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA)를 이용하여 분석하였다. 실험의 모든 결과는 3 회 반복 실험하여 평균 (means) ± 표준편차 (standard deviation)로 나타내었다. 실험 결과에 대한 통계 분석은 student’s t-test를 통해 유의성을 확인하였다 (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

결 과

1. 아프리칸 메리골드 (Tagetes erecta L.) 잎 메탄올 추출물(TE)의 세포 독성 확인

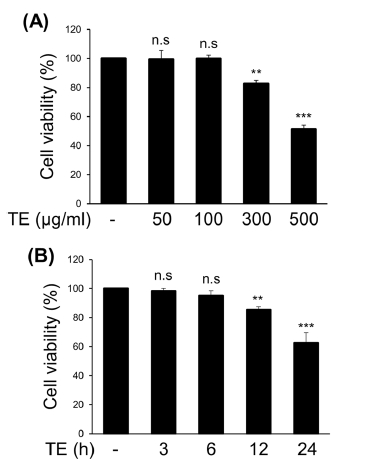

TE가 마우스 미세아교 세포주인 BV2에 세포 독성을 유발하는지 확인하기 위해 처리 시간과 농도를 다르게 한 후 trypan blue로 염색하여 살아있는 세포수를 확인하였다.

BV2 세포주에 TE를 50, 100, 300, 500 ㎍/㎖ 농도로 12시간 처리하였을 때 각각 99.4%, 99.8%, 82.5%, 51.4%의 세포생존율을 보였다 (Fig. 1A). 또한 TE를 300 ㎍/㎖ 농도로 3, 6, 12, 24 시간 처리하였을 때 각각 98.3%, 95.1%, 85.2%, 62.5%의 생존율을 보였다 (Fig. 1B). 이러한 결과를 토대로 이후 실험에서는 세포 독성이 최소화된 농도와 시간을 고려하여 100, 300 ㎍/㎖의 농도로 6 시간 처리하여 실험을 수행하였다.

Dose-, and time-dependent cytotoxicity of methanol extract of Tagetes erecta L. leaves (TE).(A) BV2 cells were treated with T. erecta extract for the indicated concentrations. After 12 h of incubation, the cytotoxicity was measured using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. (B) BV2 cells were treated with TE extract (300 ㎍/㎖) for the indicated times, and the cytotoxicity was measured using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. The results are represented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Means significantly different from the control (n.s., non-significant; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

2. 아프리칸 메리골드 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)의 신경염증 매개 단백질 발현 억제 효과

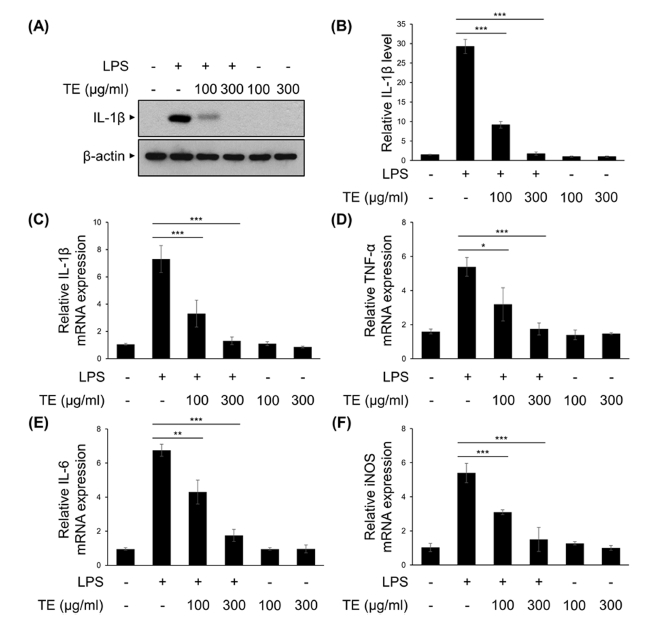

TE의 신경염증 억제 효능을 확인하기 위해, 마우스 미세아교 세포주인 BV2 세포에서 LPS로 염증반응을 유도하여 대표적인 염증성 사이토카인인 IL-1β의 발현량을 확인하였다. TE는 LPS를 처리하기 30 분 전에 100, 300 ㎍/㎖로 전처리 하였고, LPS는 50 ng/㎖의 농도로 6 시간 처리하였다. TE와 LPS를 함께 처리하였을 때 IL-1β의 단백질 발현량은 LPS 단독 처리군과 비교하여 농도의존적으로 감소하는 것을 확인할 수 있었다 (Fig. 2A and Fig. 2B).

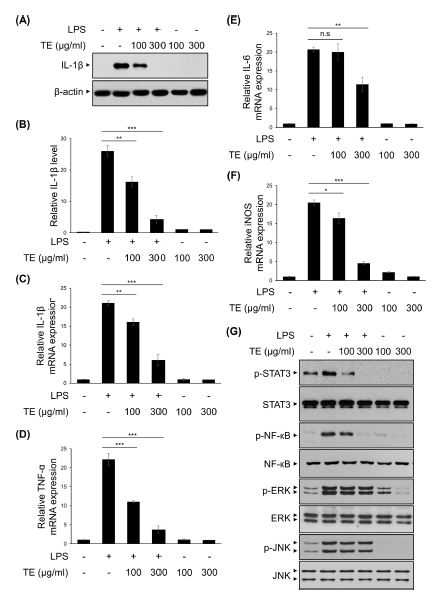

The effect of methanol extract of Tagetes erecta L. leaves (TE) in the protein and mRNA expression of LPS-induced pro-inflammatory mediators.BV2 cells were treated with TE (100 or 300 ㎍/㎖) for 30 min, followed by the LPS (50 ng/㎖) for 6 h. (A) IL-1β and β-actin protein expression levels were analyzed by Western blot analysis. (B) The relative levels of protein bands were measured by densitometry. (C - F) IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and iNOS mRNA levels were measured using qRT-PCR. The results are represented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Means significantly different from the LPS-treated group (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

같은 실험 조건으로 처리된 BV2 세포주에서 quantitative RT-PCR의 방법으로 염증성 사이토카인 (IL-1β, IL-6)과 염증매개 인자 (TNF-α, iNOS)의 mRNA 발현량을 분석하였다. TE 100 ㎍/㎖에서 LPS 단독처리군과 비교하여 IL-1β와 TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS의 발현량이 유의하게 감소하는 것을 확인할 수 있었고, 300 ㎍/㎖에서는 대조군 수준까지 감소하는 것을 확인할 수 있었다 (Fig. 2C - Fig. 2F). 이러한 결과는 미세아교세포에서 LPS에 의해 유도되는 염증성 사이토카인을 비롯한 염증 매개 인자의 발현이 TE에 의해 억제될 수 있음을 보여준다.

3. 아프리칸 메리골드 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)의 신경염증 매개전사인자 활성 억제

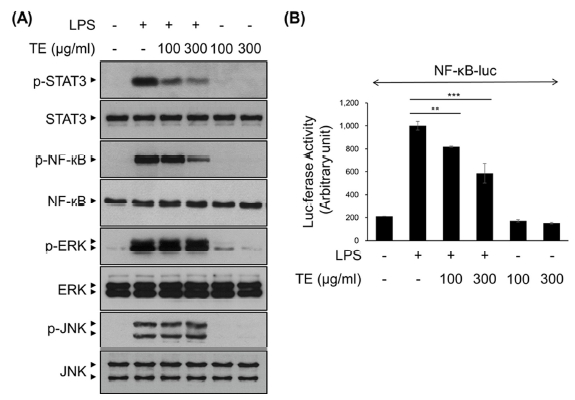

염증성 사이토카인과 염증 매개 인자에 대한 TE의 발현 억제 기전을 확인하기 위해, LPS에 의해 미세아교세포에서 활성화되는 것으로 알려진 NF-κB와 STAT3, MAPKs 등의 전사인자들의 활성을 확인하였다 (Yu et al., 2020).

TE는 LPS를 처리하기 30 분 전에 100, 300 ㎍/㎖의 농도 수준으로 전처리 하였고, LPS는 50 ng/㎖의 농도로 30 분간 처리하였다. 이후 Western blot을 수행하여 STAT3, NF-κB, ERK, JNK의 인산화를 확인하였다 (Fig. 3A). STAT3와 NF-κB의 인산화는 TE의 처리 농도에 따라 농도의존적으로 감소하는 경향을 보였으나, ERK와 JNK의 인산화는 변화를 보이지 않았다 (Fig. 3A).

The effect of methanol extract of Tagetes erecta L. leaves (TE) in LPS-induced NF-κB, STAT3 and MAPKs signaling pathway.(A) BV2 cells were treated with TE (100 or 300 ㎍/㎖) for 30 min, followed by the LPS (50 ng/㎖) for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) BV2 cells were transfected with NF-κB-luciferase reporter vectors. After 24 h, cells were pretreated with TE (100 or 300 ㎍/㎖) for 30 min, followed by the LPS (50 ng/㎖) for 6 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity. The results are represented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. n.s., nonsignificant. Means significantly different from the LPS-treated group (**p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001).

TE의 LPS에 의해 유도되는 NF-κB 전사활성 억제 효과를 확인하기 위해 luciferase vector를 이용한 reporter gene assay를 수행하였다. Fig. 3B의 결과에서 NF-κB의 전사활성은 TE의 처리 농도에 따라 농도의존적으로 감소하였다. 특히, TE 300 ㎍/㎖ 처리군에서는 LPS 단독 처리군과 비교하여 NF-κB의 전사활성은 40% 정도 감소하였다 (Fig. 3B). 이러한 결과는 TE가 STAT3와 NF-κB 신호전달 기전 억제를 통해 염증성 사이토카인과 염증 매개 인자의 발현을 조절할 가능성을 보여준다.

4. Primary microglia에서 아프리칸 메리골드 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)의 신경염증 억제 효과

실제 중추신경계에서의 TE의 신경염증 억제 효과를 검증하기 위해 마우스의 뇌에서 primary microglia를 분리·배양하여 실험에 사용하였다.

Primary microglia에 TE를 100, 300 ㎍/㎖의 수준으로 전처리 하였고, 30 분 후 LPS를 50 ng/㎖의 농도로 6 시간 처리하여 IL-1β의 단백질 발현량을 확인하였다 (Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B). 그 결과 BV2 세포주를 이용한 실험에서와 같이 TE의 처리 농도에 따라 농도의존적으로 IL-1β의 단백질 발현량이 감소하였다.

The effects of methanol extract of Tagetes erecta L. leaves (TE) on LPS-induced neuroinflammation in primary microglia.Primary microglial cells were treated with TE (100 or 300 ㎍/㎖) for 30 min, followed by the LPS (50 ng/㎖) for 6 h. (A) IL-1β and β-actin protein expression levels were analyzed by Western blot analysis. (B) The relative levels of protein bands were measured by densitometry. (C - F) IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and iNOS mRNA levels were measured using qRT-PCR. (G) Primary microglial cells were treated with TE (100 or 300 ㎍/㎖) for 30 min, followed by the LPS (50 ng/㎖) for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. The results are represented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Means significantly different from the LPS-treated group (n.s., non-significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

또한 같은 조건으로 처리한 primary microglia에서 염증성 사이토카인과 염증 매개 인자의 mRNA 발현량을 확인하였는데, TE 100 ㎍/㎖에서 LPS 단독처리군과 비교하여 IL-6를 제외한 IL-1β와 TNF-α, iNOS의 발현량은 유의하게 감소하였다 (Fig. 4C - Fig. 4F). 또한, TE 300 ㎍/㎖에서는 LPS 단독처리군과 비교하여 IL-1β와 TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS의 발현량이 크게 감소하였다 (Fig. 4C - Fig. 4F).

추가적으로 이러한 유전자의 발현 조절 메커니즘이 BV2 세포주에서와 일치하는지 확인하기 위해 MAPKs와 NF-κB, STAT3의 인산화 정도를 Western blot으로 확인하였다 (Fig. 4G). Primary microglia에 TE를 각각 100, 300 ㎍/㎖로 전처리 하였고, 30 분 후 LPS를 50 ng/㎖의 농도로 30 분 처리하였다. BV2 세포주 실험에서와 마찬가지로 TE는 primary microglia에서 LPS에 의해 증가된 STAT3와 NF-κB의 인산화를 억제하였으나, ERK와 JNK의 인산화는 억제하지 않았다 (Fig. 4G).

이러한 결과는 TE가 primary microglia에서 LPS에 의해 유도되는 염증성 사이토카인과 염증 매개 인자의 발현은 STAT3와 NF-κB 억제를 통해 조절할 수 있음을 보여준다.

고 찰

미세아교세포와 별아교세포를 포함하는 glia 세포는 신경염증과 퇴행성 뇌신경질환의 병리 기전에서 다양한 염증성 사이토카인의 분비와 아밀로이드 β (Amyloid β; Aβ), 타우 (Tau) 및 α-synuclein과 같은 단백질과 밀접하게 상호작용함으로써 신경염증 반응에서 중심적인 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다 (van Rossum and Hanisch, 2004).

알츠하이머병 환자의 뇌조직에서 IL-1β의 발현이 증가되어 있으며, 이들은 Aβ plaque 형성에 중요한 역할을 한다 (Ng et al., 2018). Aβ plaque는 미세아교세포의 활성을 유도하게 되며, 이는 다시 IL-1β의 발현을 증가시키는 피드백을 형성하게 된다 (Ng et al., 2018). 또한 IL-6가 알츠하이머병 환자의 혈청과 뇌척수액에서 증가되어 있고, 이는 신경염증 반응과 밀접하게 관련되어 있다는 연구 결과도 있다 (Ng et al., 2018).

TNF-α 역시 알츠하이머병에서 매우 중요한 염증 매개 인자인데, TNF-α 수용체인 TNFR1이 결핍된 마우스는 해마에서 미세아교세포의 활성이 완화되고 인지기능이 호전되는 것이 보고되었다 (Decourt et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2018). TNF-α는 γ-recretase의 활성과 β-secretase (BACE1)의 생성을 증가시켜 Aβ의 생성을 증가시키는 것으로도 알려져 있다 (Decourt et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2018).

STAT3는 IL-6, NF-κB는 IL-1β와 TNF-α 등의 발현을 조절하는 전사인자이며, 특히 NF-κB 저해제가 TNF-α로 인해 유도되는 BACE1의 전사 과정을 억제하여 Aβ 생성 역시 억제되었다는 연구도 있다 (Thawkar and Kaur, 2019). 따라서 NF-κB와 STAT3 같은 전사인자 활성 저해와 염증성 사이토카인 및 염증 매개 인자의 저해는 신경염증 및 퇴행성 뇌신경질환의 치료 방법이 될 수 있는 가능성이 있다.

본 연구 결과 아프리칸 메리골드 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)은 100 ㎍/㎖의 농도보다 300 ㎍/㎖ 농도에서 더 크게 LPS에 의해 유도된 STAT3와 NF-κB의 인산화를 억제하였으며, 이를 통해 염증성 사이토카인과 염증 매개 인자의 발현을 감소시켰다 (Fig. 2 - Fig. 4).

아프리칸 메리골드 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)에서는 19 개의 phytochemical이 발견되었는데, 주요 생리활성 물질로는 테트라데칸산 (tetradecanoic acid)과 2,6,10-trimethyl-14-ethylene-14-pentadecene, n-hexadecanoic acid, 15-hydroxypentadecanoic acid, 식물성 스테롤의 일종인 스티그마스테롤 (stigmasterol)이 보고된 바 있다 (Shetty et al., 2015).

이들 중에서 n-hexadecanoic acid는 세포막 인지질의 에스테르 결합 가수분해로 인한 지방산의 방출을 억제함으로써 염증 반응을 억제한다는 연구가 보고된 바 있다 (Aparna et al., 2012).

또한 스티그마스테롤은 프로게스테론 (progesterone)과 에스트로겐 (estrogen), 코르티코이드 (corticoid) 등의 호르몬을 비롯한 비타민 D3의 합성에 필요한 전구체 혹은 중간 물질로 염증 관련 연구가 비교적 많이 알려져 있다 (Sundararaman and Djerassi, 1977; Kametani and Furuyama, 1987). 콜라겐에 의해 유도된 관절염 마우스 모델에서 스티그마스테롤은 IκBα와 p38 MAPK의 인산화를 억제함으로써 IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, COX-2의 발현을 감소시켜 항염 효능을 보였다 (Khan et al., 2020). 알츠하이머병 마우스 모델을 이용한 연구에서 스티그마스테롤이 미세아교세포의 활성화를 감소시키고 염증성 사이토카인의 양을 억제함으로써 신경염증 억제와 인지기능 개선 효과를 보였다는 보고가 있다 (Jie et al., 2022). 이외에도 천식과 알러지성 피부염에서 항염 효능이 있는 것이 보고되었다 (Antwi et al., 2017; Antwi et al., 2018).

이러한 연구들은 본 연구 결과에서 확인한 아프리칸 메리골드 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)의 항염 효능이 스티그마스테롤의 효과일 것이라는 추측에 힘을 실어주지만, 다른 지표 성분들의 항염 효능 역시 완전히 배재할 수는 없다. 따라서, 본 연구 결과에서 사용된 아프리칸 메리골드의 지표 성분 분석 및 각 지표 성분의 항염 효능에 대한 연구 역시 추가적으로 수행되어야 할 것이다.

본 연구 결과는 아프리칸 메리골드 잎 메탄올 추출물 (TE)의 LPS에 의해 유도된 신경염증 억제 효능을 밝힌 첫 논문으로, 추가적인 연구를 통해 퇴행성 뇌신경질환의 병리에 중요한 작용을 하는 것으로 알려진 만성 신경염증을 제어하는 치료제로 개발될 수 있는 가능성을 제안한다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 한국연구재단(과제번호:NRF-2021R1A2C1008170)과 KRIBB Initiative Program, 과학기술정보통신부 및 정보통신기획평가원의 지역지능화혁신인재양성사업(IITP-2023-00260267)의 지원에 의하여 이루어진 결과로 이에 감사드립니다.

References

-

Antwi AO, Obiri DD and Osafo N. (2017). Stigmasterol modulates allergic airway inflammation in guinea pig model of ovalbumin-induced asthma. Mediators of Inflammation. 2017:2953930. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/mi/2017/2953930/, (cited by 2023 May 30).

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2953930]

-

Antwi AO, Obiri DD, Osafo N, Essel LB, Forkuo AD and Atobiga C. (2018). Stigmasterol alleviates cutaneous allergic responses in rodents. BioMed Research International. 2018:3984068. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2018/3984068/, (cited by 2023 May 30).

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3984068]

-

Aparna V, Dileep KV, Mandal PK, Karthe P, Sadasivan C and Haridas M. (2012). Anti-inflammatory property of n-hexadecanoic acid: Structural evidence and kinetic assessment. Chemical Diology and Drug Design. 80:434-439.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01418.x]

- Dasgupta N, Ranjan S, Saha P, Jain R, Malhotra S and Saleh AM. (2012). Antibacterial activity of leaf extract of Mexican marigold(Tagetes erecta) against different gram positive and gram negative bacterial strains. Journal of Pharmacy Research. 5:4201-4203.

-

Decourt B, Lahiri DK and Sabbagh MN. (2017). Targeting tumor necrosis factor alpha for Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 14:412-425.

[https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205013666160930110551]

-

Dickson DW, Lee SC, Mattiace LA, Yen SHC and Brosnan C. (1993). Microglia and cytokines in neurological disease, with special reference to AIDS and Alzheimer's disease. Glia. 7:75-83.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.440070113]

-

Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y and Kreutzberg GW. (1995). Microglia: Intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Research Reviews. 20:269-287.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0173(94)00015-H]

-

Jacobs AH, Tavitian B and Consortium I. (2012). Noninvasive molecular imaging of neuroinflammation. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow Metabolism. 32:1393-1415.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2012.53]

-

Jie F, Yang X, Yang B, Liu Y, Wu L and Lu B. (2022). Stigmasterol attenuates inflammatory response of microglia via NF-κB and NLRP3 signaling by AMPK activation. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 153:113317. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0753332222007065, (cited by 2023 May 30).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113317]

-

Kametani T and Furuyama H. (1987). Synthesis of vitamin D3 and related compounds. Medicinal Research Rreviews. 7:147-171.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/med.2610070202]

-

Khan MA, Sarwar AHMG, Rahat R, Ahmed RS and Umar S. (2020). Stigmasterol protects rats from collagen induced arthritis by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines. International Immunopharmacology. 85:106642. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1567576920300254, (cited by 2023 May 30).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106642]

-

Kumar V. (2019). Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of neuroinflammation. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 332:16-30.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.03.012]

-

McGeer PL, Itagaki S, Boyes BE and McGeer EG. (1988). Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease brains. Neurology. 38:1285-1285.

[https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.38.8.1285]

-

Ng A, Tam WW, Zhang MW, Ho CS, Husain SF, McIntyre RS and Ho RC. (2018). IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and CRP in elderly patients with depression or Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 8:12050. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-30487-6, (cited by 2023 May 30).

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30487-6]

-

Pratheesh V, Benny N and Sujatha C. (2009). Isolation, stabilization and characterization of xanthophyll from marigold flower-Tagetes erecta-L. Modern Applied Science. 3:19-28.

[https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v3n2p19]

- Shetty LJ, Sakr FM, Al-Obaidy K, Patel MJ and Shareef H. (2015). A brief review on medicinal plant Tagetes erecta Linn. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 5:091-095. https://japsonline.com/abstract.php?article_id=1686&sts=2, (cited by 2023 May 30).

- Sing Y, Gupta A and Kannojia P. (2020). Tagetes erecta (Marigold)-A review on its phytochemical and medicinal properties. Current Medical and Drug Research. 4:201. http://globalscitechocean.com/ReportFile/8eca609ffd344150a38a1df0c02efa32.pdf, (cited by 2023 May 30).

-

Sundararaman P and Djerassi C. (1977). A convenient synthesis of progesterone from stigmasterol. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 42:3633-3634.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jo00442a044]

-

Thawkar BS and Kaur G. (2019). Inhibitors of NF-κB and P2X7/NLRP3/Caspase 1 pathway in microglia: Novel therapeutic opportunities in neuroinflammation induced early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 326:62-74.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.11.010]

-

van Rossum D and Hanisch U. (2004). Microglia and the cerebral defence system. In Herdegen T and Delgado-García J. (eds.). Brain damage and repair. Springer. Dordrecht, Netherlands. p.181-202.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2541-6_12]

-

Venneti S, Wiley CA and Kofler J. (2009). Imaging microglial activation during neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 4:227-243.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-008-9142-2]

-

Xu LW, Wang GY and Shi YP. (2011). Chemical constituents from Tagetes erecta flowers. Chemistry of Natural Compounds. 47:281-283.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10600-011-9905-5]

-

Yamanaka M, Ishikawa T, Griep A, Axt D, Kummer MP and Heneka MT. (2012). PPARγ/RXRα-induced and CD36-mediated microglial amyloid-β phagocytosis results in cognitive improvement in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 32:17321-17331.

[https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1569-12.2012]

-

Yu CI, Cheng CI, Kang YF, Chang PC, Lin IP, Kuo YH, Jhou AJ, Lin MY, Chen CY and Lee CH. (2020). Hispidulin inhibits neuroinflammation in lipopolysaccharide-activated BV2 microglia and attenuates the activation of Akt, NF-κB, and STAT3 pathway. Neurotoxicity Research. 38:163-174.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12640-020-00197-x]